The Credits

“Ahsoka” Cinematographer Eric Steelberg on Lensing a Rebel Jedi’s Journey Through Time & Space

For Ahsoka cinematographer Eric Steelberg, lensing the latest live-action Star Wars series was a dream come true. Growing up in thrall to George Lucas’s original trilogy, Steelberg would find himself on set while filming the new series, surrounded by massive spaceships both practical and virtual (the latter thanks to Industrial Light & Magic’s LED immersive soundstage the Volume), astonished by his own job.

“You’re sitting there trying to figure this out and tell the story because it is a job, but then what you’re watching takes you aback. Like, I can’t believe we’re doing this,” Steelberg says.

The new series, the first live-action Star Wars show to spring from one of the franchise’s animated series (Star Wars: Rebels), follows its titular heroine, the rebel Jedi Ahsoka Tano (Rosario Dawson), and the return of a terrifically powerful adversary (Grand Admiral Thrawn, played by Lars Mikkelsen, who also voiced him in Rebels) in the aftermath of the fall of the Galactic Empire. Ahsoka’s allies are chiefly her former padawan Sabine Wren (Natasha Liu Bordizzo), her trusty droid Huyang (voiced by David Tennant), and General Hera Syndulla (Mary Elizabeth Winstead). Along with Thrawn, her chief antagonists are the formidable Baylan Skoll (the late Ray Stevenson), his protege Shin Hati (Ivanna Sakhno), and an assortment of bad guys, from droids to assassins, all working in concert to aid the return of Thrawn. Oh, and then there’s the thrilling arrival of Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen, reprising his role), who featured prominently in episode 5, “Shadow Warrior,” as he and Ahsoka tangled and tumbled through their past together in a deeply satisfying trip down memory lane.

We spoke to Steelberg about fulfilling a lifelong dream, from lightsaber duels to speeder bikes and all manner of Star Wars-styled action in between.

As a Star Wars fan, which I imagine so many of the folks working on Ahsoka are, what was it like taking on the responsibility of stepping into arguably the most storied franchise of them all?

It’s a lot of responsibility to take on. What if my fandom doesn’t translate through my work? At the same time, that amount of excitement and fear turns into healthy creative fuel.

Ahsoka has narrative overlap with The Mandalorian, but it’s a grander, more expansive story. Can you talk about the look and feel of the series?

The Mandalorian set the bar very high from what’s to be expected from a TV version of Star Wars. Your barrier for entry is already higher than I’ve ever experienced. And you’ve got the expectations of fans from the movies. I understand wanting the same level of quality. If we’re doing live-action, we’re doing live-action, and I don’t care what the budget is. All that matters is the final result. So people want those big, sprawling epic stories. They want high production value. They want a certain look. So that’s how I went into the project; we’ve all got the expectations of movie-level quality visuals, the technical expectations that were established in The Mandalorian and The Book of Boba Fett and Obi-Wan Kenobi. So how do we achieve that but make it feel different?

How did you?

I started with Dave Filoni in prep about how we expand upon those expectations technically and creatively. We referenced the movies—both the originals and the more recent ones—and then it was a lot of references to Akira Kurosawa movies, which was a well-documented influence on both George Lucas and Dave. There are tonal things, letting things play out in wide shots that give it a sense of scale. That was our jumping-off point. Then, it was working with our art departments on what we could create that would show on screen in the best way possible. And this is a different story, based on the Star Wars: Rebels animated series. There are influences, even shots, taken from that. And then, for me, it’s also about how you capture that feeling of this being Star Wars?

How would you describe a shot that feels like Star Wars?

Honestly, it comes down to a kind of gut feeling because some of its editing, some of its production design, some of its framing, and some of its lighting. Also, Star Wars is always widescreen, right? And what kind of screen? It’s always anamorphic. So that’s the most basic version, the visual starting point. From there, looking at the cinematography, for me, it’s the original three movies. That’s what I grew up on. That’s what I fell in love with. I’m always thinking of parallel moments in the original movies we can reference. At the same time, those movies were made in the late 70s and early 80s, so how do you keep that very polished, formal lighting style with the expectations of a modern audience that wants energy and pace? So that was just taken on a scene-by-scene, episode-by-episode process. But overall, it’s very composed, more classically lit, there’s no handheld camera work, everything is very deliberate. Everything is very planned and very designed.

Dipping into your episodes that have aired, can you pull out a sequence or moment that stood out for you?

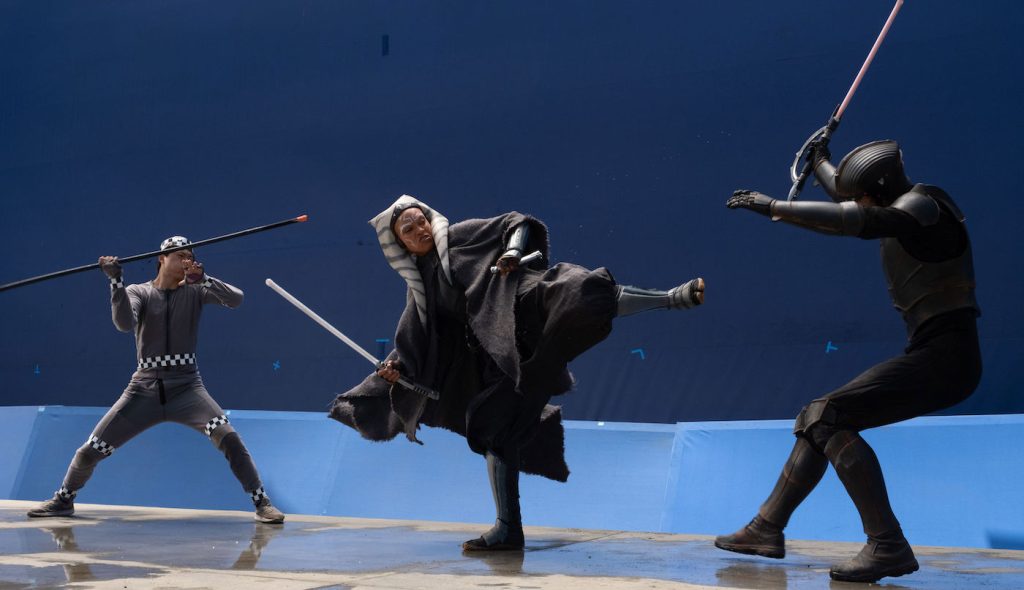

The things that are classic Star Wars are the things that really got me. Sabine on a speeder bike going down the highway. That was amazing to try and give that an energy and realism I felt like we hadn’t seen before. And then the lightsaber fights, like the end sequence between Shin [Ivanna Sakhno] and Sabine—I was like, Oh my God, I’m shooting a lightsaber fight. This is amazing, and I can’t screw this up.

Even though this is the career you’ve chosen and worked hard at for years, it must still be surreal to go from being a fan of Star Wars to filming a lightsaber duel.

Just being in the cockpit of a spaceship, you know? Having those Star Wars conversations about rebels and shooting in the hangar bay and having these Star Wars ships around, which we did in the Volume in our virtual environment. It’s incredible. It doesn’t get old. You’re sitting there trying to figure this out and tell the story because it is a job, but then what you’re watching takes you aback. Like, I can’t believe we’re doing this; we’re adults playing with lightsabers, but being very earnest and serious about the best way to do it. It’s really hard, and it’s really fun. And there’s a tremendous amount of pride you get from doing something you have such an affinity for.

Ahsoka also benefits from having great villains—it’s very easy to root for Ahsoka, Sabine, Hera, and the droid Huyang [David Tennant]—but then you’ve got these great antagonists in the late Ray Stevenson as Baylan Skoll and Ivanna Sakhno as Shin.

We do. The casting is phenomenal. All the actors are not only perfect in the roles, but all good people, fun to be around, and love their characters. In Star Wars, the villains are sometimes more fun than the protagonists. Ray was fantastic. Phenomenal. Nobody else could do that role. One of my favorite things about my job is I love working with actors. I love watching actors really get into their characters. Ray would be like, ‘How was it?’ And you’d say, great! And you’d hesitate and say, ‘You know, we just missed this one look,’ but you don’t really want to say anything because they did such a good job. And you think maybe you can just work around it, but Ray would say, ‘What do you guys need?’ We’d show him, and he’d just nail it.

There’s a begrudging respect between Baylan and Ahsoka, which reads almost like an intimacy that, so far, has made this a fun series.

I was really proud of episode four. It was really very challenging. Over half of the episode is lightsaber fights, and how do you keep that interesting? But we did. I remember in prep, I read the three or four scripts that were ready, and I remember thinking, ‘My God, how are we going to do this?’ It’s so complex, and what was being asked visually was off the charts for me. You might as well have said let’s actually shoot in space; it was so different from anything I’d ever done, too. I’d done some second unit in The Mandalorian season two, but I’d never done anything like this. But for everyone involved, the fact that it was Dave Filoni asking for it, it might as well have been George Lucas. It’s Dave’s creation, and he’s such a smart, talented, nice person that you want to give him everything he wants as a director. He’s so likable, he’s such a nice guy, you just have this desire to make him happy. Everybody was like, we have to figure this out.

It must help that everybody involved is such a huge Star Wars fan.

It’s funny, my crew and everybody else [on set] acts very professional while we’re working, and then you find out when you’re done that you’ve got these big Star Wars geeks with you. They’re like, “I didn’t want to say anything, but I was really needing out when we did this or that.” These are ultra huge fans, but if you weren’t a huge fan, you’d never make it through this because it’s the hardest work I’ve ever done. The level of passion and skill that you get from people is mind-blowing. It’s not even like playing with the All-Star team; it’s like being on the Olympic team.

Ahsoka is streaming on Disney+

For more on all things Star Wars, check out these stories:

Donald Glover’s “Lando” Series Will be a Movie Instead

A Battle Through Time With & Against Anakin Skywalker in “Ahsoka” Episode 5

“Ahsoka” First Reactions: Rosario Dawson And Natasha Liu Bordizzo Shine in Latest “Star Wars” Series

Featured image: (L-R): Marrok (Paul Darnell) and Ahsoka Tano (Rosario Dawson) in Lucasfilm’s STAR WARS: AHSOKA, exclusively on Disney+. ©2023 Lucasfilm Ltd. & TM. All Rights Reserved.